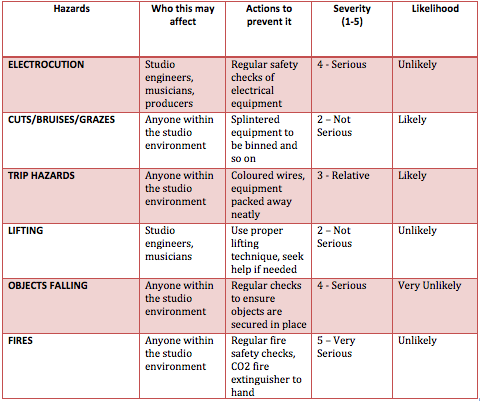

In this blog, I’m going to be talking about a track that me, Will Allman and Lewis Spencer wrote back a few years and eventually recorded. I just wanted to upload a blog to explain what went on in that session and how we went about it.

For this recording assignment, we had to record a selected song without help from any tutors, and keep a log of what happened along the way.

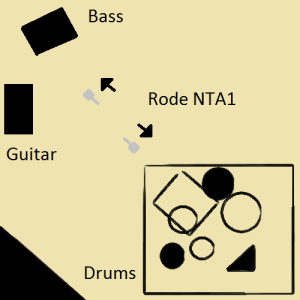

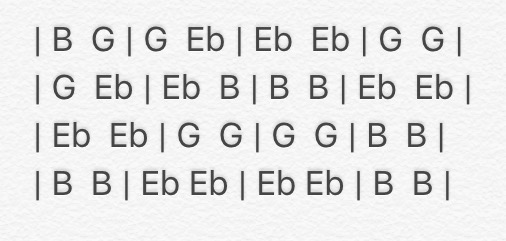

It is an entirely instrumental piece. The song is meant to symbolise being trapped and trying to escape. We came to the decision that the drums should be recorded first, and we should mic the kit in this way: 2 overhead mics (Rode NTA1 Condensers), 1 snare drum mic (SM57) and 1 bass drum mic (AKG D112). These mics were decided on because we thought they’d be the best quality. The two Rode Condenser mics because they pick up a large amount of frequencies, meaning it would pick up the whole kit in one. The SM57 mic is good at picking mid to high frequency sounds which means it is good for a snare drum as it would pick up the high frequency pop sound a snare makes and finally the AKG D112 is a bass mic, therefore it picks up low frequencies and so it would be perfect for use on a bass drum. The AKG was linked to channel 1, the SM57 to channel 2, and the Rode Condensers to channels 3 & 4. I then quickly soundchecked the kit to make sure everything was coming through, which it was. But there was a slight odd problem in that even though the bass drum mic was linked to channel 1, it was coming through channel 2. But then we quickly discovered that the leads in the back of the mixing desk were mixed around, channel 1 was plugged into 2 and vice versa. After sorting that problem we decided to go for a take, Lewis and Will came into the recording booth and played along with me unplugged so that I could keep the timing right, as some parts are funnily timed. I messed up about half way through the song on my first take, so I had another go. The 2nd time round seemed fine, until I went back round to the studio to find that channel 4 wasn’t rooted, so Overhead Mic Right didn’t record anything. So once again after sorting the problem we went back into the live room and tried a 3rd take, which went all to plan without any problems. We then turned all of the levels down and proceeded to pack away for the day as our 2 hour studio time had come to an end. Before leaving the studio, I quickly normalized all of the tracks, and saved the file.

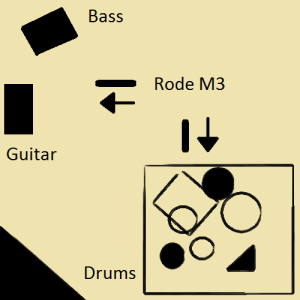

On our second studio session we tried to kill two birds with one stone and record the bass and guitar at the same time. We decided to record the bass through DI (Direct Input) as we didn’t want any effects on the bass at this time, and we could EQ it further into the project. We used the SM57 mic again to record the guitar amps as it has mid to high sensitivity which would make it ideal for a guitar amp. We then had to go about sending my drum tracks through to Will & Lewis in the recording booth, but we had a slight problem where we could only locate 1 set of headphones. So we decided to give Will the one set of headphones, and send the drum tracks to both the speakers in the recording booth and the headphones that Will would be using, so then they could both hear, and play along to the track. This was then followed by another error which we had to sort out, the signal that was coming through the speaker was very quiet meaning that Lewis couldn’t hear what was going on, so after they had a trial run through to see how it went, Lewis said that he couldn’t hear anything, so we went about trying to figure out how to make the signal louder. After about five minutes of brain storming we figured out how to do it, meaning that Lewis could now hear the drums he’d be playing along to. They then took another take in which Lewis messed up, resulting in a third take where everything went smoothly. We then packed away all of the mics, normalized the tracks which had just been recorded, and saved the file for the next session.

At the next studio session we began by listening to the track, also at this point, Lewis felt unimpressed with his guitar take from the last session and requested that we re-do it. We set up for Lewis to re-record his parts the same way we had previously. All went well and he managed to nail his parts in one take. We then simple tidied the mics away. Now came the part of the process where we alter the product in any way we please. We deleted all of the unwanted takes and then got to work on detail. Such as compression, effects, editing etc. We decided that the drums would be an ideal place to begin with, and started with noise gating the kick drum. We did this by going to the inserts section whilst having the kick drum layer selected, and chose ‘Gate’. From this point on Will took charge to gate the drums as we felt he had a better knowledge of how to get things sounding nice and smooth. We got a nice sounding kick drum, gated with the following settings: -26.9 Threshold, and 0.1 Attack. This gave a nice booming sound for the bass drum, with no spill from any other drum or cymbals. We then continued to gate the snare drum, as it had a lot of spill coming from the hi-hat cymbals. We managed to remove the cymbals, and get a nice popping sound from the snare, gating it with: -38.7 Threshold, 332 Release, and 0.1 Attack. We then followed it up by gating the overhead mics. Left mic was gated with: -53.1 Threshold, and 525 release. Right mic was gated with: -44.9 Threshold, and 302 release. This made the toms sound really clear and crisp, whilst making the cymbals louder and more effective. The project was then saved.

The week after we began work on the other instruments (bass and guitar) and also the harmony vocals. We didn’t need to put a noise gate on the bass as it went through DI which means there would be no other sound but the bass guitar itself. However, we did feel the need to add some compression to make it sound clearer. After being recommended some presets by some of the other students in the class, we made the decision to go with the preset “Percussion 2” as it made the bass louder, smoother and more bassy. We then continued on to do the same with the guitar compression and ended up choosing the “Light Jazz Vocals” preset as it made the guitar louder and cleaner. After the compression stage, Lewis informed us that most of the guitar is supposed to be distorted, but he recorded it in a clean setting. So we copied his guitar track onto another layer, and added distortion to the parts which he told us to. We did also decide decide to get Benji to drop some vocals over one section of the song in which he copies the lead line. We recorded this through a Rode NTA1 Condenser Mic in one take and put the Light Jazz Vocals preset on this too.

After all of this process was complete we listened back to the track to see how it sounded. Under close inspection we noticed that the bass was a 16th note behind everything else, but we didn’t have enough time to change it. We then saved the project, did an audio mixdown of the track and sent it to all of our email addresses.

If I could re-do the project, I would definitely do things a lot different, for instance I would figure out the tempo to the track and play along to a click to avoid any timing problems, and I would also request to record the guitars, vocals and bass individually, instead of trying to do it all in one go. On reflection, the outcome of this project was very poor in my opinion. The playing is sloppy, it sounds very poor and I don’t think anyone’s heart was in the project as by the end, nobody really seemed enthusiastic about it what so ever. I would completely re-do everything if we were to try and revive this track, although the thought of it is very unappealing.